Below is an essay I presented to the Chicago Literary Club on February 27th, 2023. Please note that this essay was written to be read aloud to an audience presumed to be unaware of the incident or its enduring legend.

Max and the Flyswatter

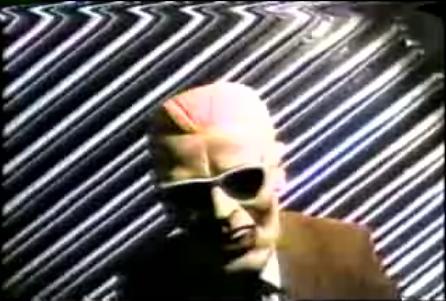

On Sunday, November 22nd, 1987, Chicagoans gathered ‘round their TV sets to watch WGN’s 9 O’clock News. At 9:14 pm, sportscaster Dan Roan’s segment was interrupted by a black screen, after which a poorly recorded videotape appeared of a man disguised as Max Headroom (a fictional TV character who was a sensation in both America and the United Kingdom). The man wore a mask that obscured his face while bobbing up and down in front of a rotating, corrugated metal panel.

There was no audio transmission save for a staticky buzz.

Within 17 seconds, WGN engineers regained control of the signal, allowing Dan Roan and his bemused co-hosts, one of whom was Chicago Literary Club member Robert Jordan, to continue their reporting.

It turns out that Roan was as bewildered as his audience, and the best explanation he could muster was that the station’s computer “took off and went wild.”

The rest of the newscast continued without incident.

Two hours later, our masked man struck again: His next target was WTTW’s late-night broadcast of Dr. Who. This transmission was much more successful: For one thing, the audio worked. For another, there were no engineers on duty at the Sears Tower, which was the location of the station’s transmitter. Channel 11’s studio technicians tried, and failed, to regain control of their signal and were forced to watch helplessly as “Max” once again seized the airwaves, using his electronically distorted voice to expound on a range of subjects. Chuck Swirsky, a sports announcer on WGN radio, was a particular target of his wrath, as was the network itself.

Max also sang, hummed, moaned, uttered scatological jokes, simulated defecation, brandished what the press euphemistically described as a “marital aid,” and, for his grand finale, bent over a table while a woman in a German barmaid costume flogged his bare buttocks with a flyswatter.

The transmission ended after about a minute and 22 seconds. Channel 11’s programming resumed and remained undisturbed for the rest of the evening.

By the next morning, news of the hijacked signals had spread and, for a brief period, dominated local and national news cycles. Spokespersons for both stations assured the public that steps had been taken, and an FCC spokesman issued a stern warning to the perpetrators.

Public sentiment ranged from amused to apoplectic. Fans of Dr. Who were particularly peeved, as WTTW was their only source of the British series, and they had lost close to a minute and a half of a precious episode.

The media coverage and public bewilderment did not last long, however. Three days after the incident, Mayor Harold Washington died unexpectedly. The media redirected its attention to the mayor’s life, death, and funeral, along with the resulting shenanigans of Chicago’s city council.

However, many people remained interested in the case, federal regulators being first among them: Interference with broadcast signals is illegal and the FCC launched an investigation. They were joined by the FBI, which had access to more sophisticated technology and could thus more thoroughly analyze the broadcasts.

Curiously, and despite the early media blitz and federal involvement, the official investigation came to nothing. In a 2013 interview with Vice, Dr. Michael Marcus, an FCC investigator with a history of success in tracking down broadcast pirates, explained that while he was eager to pursue the hacker, he had a problem: Marcus was in Washington, and his FCC colleague in Chicago had his own ideas about the case. Much to Marcus’s frustration, the Chicago-based agent dropped the ball on several promising leads.

The reasons for the field agent’s reticence aren’t clear, though Marcus suggests that the local investigator lacked experience in piracy cases and felt out of his depth. The investigation stalled, and no suspect was ever named.

Had the interest in this case been relegated to the media and law enforcement, the signal hijacking might have faded out of our collective cultural memory. That didn’t happen; public preoccupation with hacking has only increased. A Google search using the term “Max Headroom Incident” calls up 670,000 results. The case continues to be examined, written about, and debated in legacy and online media.

This continued fascination can be attributed to the other group of people who maintained a keen interest even after the media furor died down: Namely, the hacker community. This motley assortment of computer geeks, telephone phreakers, and broadcast pirates regarded the signal disruption as a praiseworthy accomplishment. They felt a strong sense of pride that one of their own had managed such a feat. These same geeks and hackers would go on to lay the foundation for the modern Internet and its corresponding online culture, so it isn’t surprising that the Max Headroom incident has continued to garner interest that has eclipsed even the initial media frenzy.

(Then too, people do love a good mystery, and the continued anonymity of the perpetrators remains a tempting rabbit hole that many people, including myself, are eager to hop into.)

While I am neither a tech geek, nor a federal agent, the hacker’s brazen audacity, inscrutable motives, perverse content, and enduring silence continue to perturb me, often at inconvenient times. While I cannot identify an individual suspect, I have strong opinions about what happened that cold, drizzly November night.

Now, I should note that a primary area of dispute among those who follow the case is whether the signal intrusion was merely a prank by an amateur “hacker” or an act of retaliation by an unhappy industry professional. The initial media reports indicated the latter, largely because regulators and station representatives were adamant that the hijacking required sophisticated technical knowledge and access to expensive, specialized equipment. It seemed unlikely that a lone-wolf hacker, even one with the requisite engineering knowledge, could have sourced the required technology.

But others are equally convinced that the intrusion was an amateur prank. These partisans maintain that the story about the necessity of costly and hard-to-get equipment was concocted by regulators and station executives who didn’t want the public to know how the signals were hijacked.

You see, contrary to public perception, the broadcast transmitters were not the hijacker’s primary target. The WGN transmitter, located on top of the John Hancock building, and the WTTW transmitter, at the Sears Tower, were fed via microwave uplinks from each studio, both miles away from downtown. The pirate disrupted these uplinks with his broadcast, which was then sent to the transmitters and beamed into the homes of Chicago residents.

In the VICE interview, Dr. Marcus dismissed the idea that the hacking required expensive or difficult-to-source hardware. He states that the microwave intrusion would have required equipment readily available to ham radio operators, along with a dish antenna that, depending on its location, could have been as small as a standard residential Direct TV dish. He also noted that while the costs could have been as much as $10,000, that number reflects the price of new equipment. Second-hand technology would have cost much less.

My position begins with a rejection of the hacker vs. professional binary. After all, the line that divides professionals from amateurs is easily blurred. Many tech enthusiasts hold regular jobs in their industries while also maintaining various hobby projects.

I believe that the primary instigator of the Max Headroom incident was not a random hacker, but a professional broadcast engineer gone rogue. The successful signal intrusions, the nature of the audio content during the second intrusion, the decision to hijack WTTW’s signal later in the evening, and the choice of a Max Headroom disguise reinforce my theory.

The motive for the signal hijack was likely professional disgruntlement. Perhaps the hacker had worked at WGN and was unhappy there. Perhaps he had applied for a job and been rejected. Whatever his situation, the content of the video suggests a personal grudge. While the more extreme on-air hijinks, such as the spanking, were silly and sophomoric, there were multiple references to WGN during a transmission that lasted only 82 seconds. The first reference to the station suggests resentment, with Max declaring, “Yeah, I think I’m better than Chuck Swirsky. Freakin’ liberal.”

About thirty seconds later, Max makes two separate references to Clutch Cargo, a children’s cartoon that had been a regular feature on WGN’s long-running Garfield Goose & Friends. Finally, he mentions “greatest world newspaper nerds.” a reference to WGN’s call letters which stand for “World’s Greatest Newspaper,” harkening back to when the company was owned by the Chicago Tribune. The frequency and specificity of these remarks suggest that “Max” had an ax to grind.

Another intriguing aspect of this case is the second transmission. Most followers of the incident agree that WGN was always the intended target. The question is why the hacker would repeat an intrusion on another network, increasing his risk of being caught. A prankster might have just dropped the project after his successful, albeit brief, disruption of WGN’s signal, but an angry man on a mission has different priorities.

I suspect that the pirate knew he was taking a gamble on the WGN transmission, hoping the engineers would be so stunned by the intrusion that it would take them a minute or two to respond effectively. When the hijacking was aborted after only 17 seconds, “Max” went to his Plan B, choosing WTTW because, being a broadcasting insider, he knew that the Sears Tower transmitter was unstaffed, allowing him enough time to run his entire video.

My final reason for believing that the hijacker was an industry professional is his choice of the Max Headroom persona. This fictional character was billed as the first computer-generated newscaster, a semi-autonomous CGI image powered by artificial intelligence. The source of the AI? A computer-generated copy of the mind of one Edison Carter, an investigative journalist operating in a dystopian society run by media oligarchs.

Max Headroom could move between television and computer screens, disrupting broadcasts and criticizing the practices of media companies and their sponsors. He and Edison Carter also allied with a couple living outside the dystopian regime, operating an unlicensed, pirate television station. It is easy to see how a disgruntled media insider might find the Headroom persona attractive.

The truth is out there, but for now, nobody is talking. The statute of limitations on prosecution for the incident ended in 1992, but it is a fair bet that a public admission could affect the hacker’s career. Since it is possible that Max and his female accomplice were in their 20s at the time of the incident, they might wait until they reach retirement age before making a public confession. Even without the threat of losing their careers, however, they may be reluctant to identify themselves because they value their privacy and don’t care to become cultural antiheroes.

Whether the truth is ever made known, or not, this story continues to be told and enjoyed, providing us all with an enduring bridge between two very different media landscapes.